A few years ago I made a Python algorithm to solve sudokus in seconds.

Seconds ? Bah, let’s do better and solve it in half a millisecond thanks to the Go programming language.

· · · | · · · | ¹ · ·

³ · ¹ | ⁷ ⁹ · | · · ·

· ⁴ · | · · · | · · ⁷

· · ⁵ | · · ⁷ | ³ · ·

⁷ · · | ⁵ · ² | · · ·

· · ⁸ | · ¹ · | ² · ·

⁶ · ⁷ | · · ⁹ | · ³ ·

· ¹ · | ² · · | · ⁵ ·

· · ⁹ | · · · | · · ⁸

We will use this sudoku as an example through this article.

The story

My grandmother loves sudoku, so I wanted to make a tool to help her find the answer.

The first step is to design an algorithm. Then, ideally one should try to create an application with computer vision to identify the numbers and then apply the algorithm. But this article will mainly focus on the algorithm.

So I wrote an algorithm for the first time 5 years ago, in Python. It was able to solve a sudoku in a few seconds. Now, I have improved it and rewritten it in Go, in order to learn this language and explore its possibilities.

Here is how to solve a sudoku in a millisecond. ⚡️

The algorithm

The objective is to fill the 9x9 grid with numbers from 1 to 9. For a given number, there should be only one occurrence in each row, column and 3x3 cell.

There are many ways to solve a sudoku.

The brute-force

Simply trying every number from 1 to 9 in each cell, independently of other cells. And when every cell is filled, verify that the rules are respected.

1 1 1 1 1 1 ¹ 1 1

³ 1 ¹ ⁷ ⁹ 1 1 1 1

1 ⁴ 1 1 1 1 1 1 ⁷

1 1 ⁵ 1 1 ⁷ ³ 1 1

⁷ 1 1 ⁵ 1 ² 1 1 1

1 1 ⁸ 1 ¹ 1 ² 1 1

⁶ 1 ⁷ 1 1 ⁹ 1 ³ 1

1 ¹ 1 ² 1 1 1 ⁵ 1

1 1 ⁹ 1 1 1 1 1 ⁸

First, try to fill every thing with ones. This isn’t a valid sudoku, so let’s change one number, the last “2”.

1 1 1 1 1 1 ¹ 1 1

³ 1 ¹ ⁷ ⁹ 1 1 1 1

1 ⁴ 1 1 1 1 1 1 ⁷

1 1 ⁵ 1 1 ⁷ ³ 1 1

⁷ 1 1 ⁵ 1 ² 1 1 1

1 1 ⁸ 1 ¹ 1 ² 1 1

⁶ 1 ⁷ 1 1 ⁹ 1 ³ 1

1 ¹ 1 ² 1 1 1 ⁵ 1

1 1 ⁹ 1 1 1 1 2 ⁸

And so on. For a game with 20 hints at the beginning, there is 9^(81-20) possibilities to explore, so… 16,173,092,699,229,880,893,718,618,465,586,445,357,583,280,647,840,659,957,609 combinations possible. Even with a 4GHz processor, it’ll take like 10^39 centuries to compute everything. Quite a long time. Let’s reduce this number.

The smart brute-force: backtracking

Basically, this is the labyrinth algorithm.

Just go right again and again. When you get stuck, go back to the previous crossroads and turn left instead of right. Then continue with the same strategy.

We start at the top left and with the smallest number possible.

2 · · | · · · | ¹ · ·

³ · ¹ | ⁷ ⁹ · | · · ·

· ⁴ · | · · · | · · ⁷

· · ⁵ | · · ⁷ | ³ · ·

⁷ · · | ⁵ · ² | · · ·

· · ⁸ | · ¹ · | ² · ·

⁶ · ⁷ | · · ⁹ | · ³ ·

· ¹ · | ² · · | · ⁵ ·

· · ⁹ | · · · | · · ⁸

The 1 doesn’t fit, but the 2 is okay. We’ll try the next cell.

2 5 · | · · · | ¹ · ·

³ · ¹ | ⁷ ⁹ · | · · ·

· ⁴ · | · · · | · · ⁷

· · ⁵ | · · ⁷ | ³ · ·

⁷ · · | ⁵ · ² | · · ·

· · ⁸ | · ¹ · | ² · ·

⁶ · ⁷ | · · ⁹ | · ³ ·

· ¹ · | ² · · | · ⁵ ·

· · ⁹ | · · · | · · ⁸

The smallest number possible to write is 5. Let’s continue, until we’re stuck.

2 5 6 | 3 4 8 | ¹ 9 ?

³ · ¹ | ⁷ ⁹ · | · · ·

· ⁴ · | · · · | · · ⁷

· · ⁵ | · · ⁷ | ³ · ·

⁷ · · | ⁵ · ² | · · ·

· · ⁸ | · ¹ · | ² · ·

⁶ · ⁷ | · · ⁹ | · ³ ·

· ¹ · | ² · · | · ⁵ ·

· · ⁹ | · · · | · · ⁸

At the end of the line, it is impossible to place a number. So let’s go back to the previous cell, with the 9. We will increase this number by one unit. Since this is not possible either, we go back to the 8 and erase the 9. For the 8, it is not possible to increase, so we delete the 8 and go back to the 4. Here it is possible to increase the 4. The next available number is 8, because 5, 6 and 7 are impossible to insert.

2 ₅ ₆ | 3 8 · | ¹ · ·

³ · ¹ | ⁷ ⁹ · | · · ·

· ⁴ · | · · · | · · ⁷

· · ⁵ | · · ⁷ | ³ · ·

⁷ · · | ⁵ · ² | · · ·

· · ⁸ | · ¹ · | ² · ·

⁶ · ⁷ | · · ⁹ | · ³ ·

· ¹ · | ² · · | · ⁵ ·

· · ⁹ | · · · | · · ⁸

This is called backtracking. Repeat the same algorithm until a solution is found.

Let’s do better

The algorithm is quite fast, but is not optimized. Indeed, it is not a good idea to start at the top left and continue in the reading direction. We can define a custom order! A good idea could be to count the number of possible digits to fit in each cell at the beginning (when the grid is empty). For example, the top left cell has 4 possibilities: 2, 5, ⁸ and 9. We can see that some cells have only one number available!

4 6 2 | 4 6 5 | · 5 6

· 4 · | · · 4 | 4 4 4

4 · 2 | 4 5 5 | 4 4 ·

4 3 · | 4 3 · | · 5 4

· 3 3 | · 4 · | 4 5 4

2 3 · | 4 · 3 | · 4 4

· 3 · | 3 3 · | 1 · 3

2 · 2 | · 5 4 | 4 · 3

3 3 · | 4 5 5 | 3 5 ·

Then, we apply the previous algorithm, beginning by the cells where there are the fewer possibilities.

· · · | · · · | ¹ · ·

³ · ¹ | ⁷ ⁹ · | · · ·

· ⁴ · | · · · | · · ⁷

· · ⁵ | · · ⁷ | ³ · ·

⁷ · · | ⁵ · ² | · · ·

· · ⁸ | · ¹ · | ² · ·

⁶ · ⁷ | · · ⁹ | 4 ³ ·

· ¹ · | ² · · | · ⁵ ·

· · ⁹ | · · · | · · ⁸

There is only one digit available : this one won’t have to change and won’t block the other numbers !

Speed here is around a couple of milliseconds in Go.

Time vs Space tradeoffs

This is a classical Computer Science thing.

Remember when I said that it is a good idea to count the number of possible digits to fit in each cell ? In fact, we can not only keep this number but the numbers themselves. We do not need to do a useless +1 and check if it is correct : just jump from 2 to 5 directly !

This will increase space complexity from 9x9 to 9x9x9 (maximum), but honestly this is nothing compared to the time we’ll save.

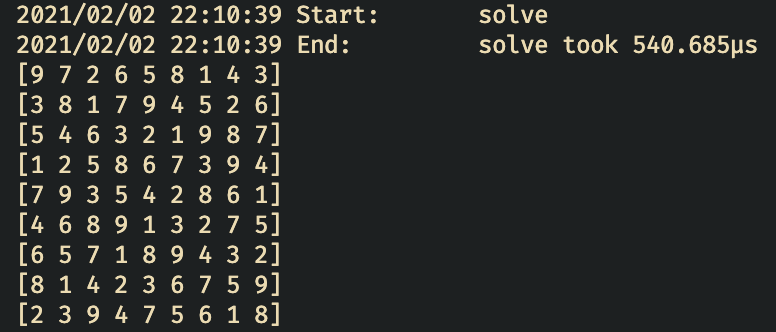

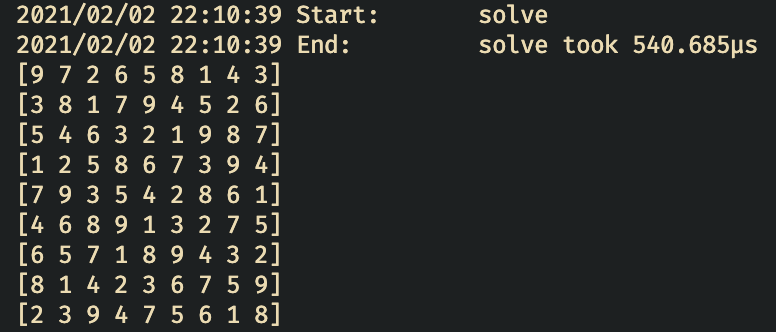

Here we are, under a millisecond.

You can see my algorithm for Python here and Go here.

Python vs. Go benchmark

Basically Go is 1000x faster than the original Python 3.9 (I haven’t tested CPython yet but honestly, this is kinda cheating + ugly).

This perfectly illustrates the differences in performance between an interpreted language and a compiled language. Although compiled, Go remains very simple (no arithmetic on pointers as in C) and benefits from all these advantages. However, just because Go is very fast does not mean that you should abandon Python. Python is very easy to use, has many useful libraries and a huge community. However, since learning machine algorithms are often resource-intensive, it might be interesting to develop the performance potential of Go.

WIP: graphs